Patrick Ian Hartley

From his design practice at his London Bridge studio, British Designer Patrick Ian Hartley produces unique, bespoke Face Corsets and neckwear for private clients in both the UK and internationally. Meticulously tailored to the wearer in leather, silk and PVC, his designs are both transforming of the face, and transformable in their form and structure.

Patrick also designs for commissioned fashion editorial as well as a private client base, designing and building work specifically around the clients facial dimensions and characteristics to specific requirements. He has designed work commissioned for personalities including Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Noomi Rapace, Elizabeth Banks Georgia May Jagger, Artist Richard Sawdon Smith, Stylists Simon Foxton, Edward Enninful, Jacob K, Jonathan Kaye to name a few. His designs are regularly showcased in leading fashion publications including AnOther Magazine, Vogue Italia/China/Germany/Turkey, V Magazine, W Magazine, Interview, The Hunger and Harpers China.

Patrick’s work has been shot by Iconic fashion photographers including Nick Knight, Rankin, Tim Walker, Steve Klein, Miles Aldridge and Roberto Aguilar. He has exhibited designs at venues including the SHOWstudio Gallery London, The Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and is collected by the Museum of Arts and Design, New York and The Wellcome Collection London and the Museum of Art Architecture and Design, Oslo.

In addition to producing collections, bespoke designs and commissions for private clients and performers, Patrick also guest lectures regularly at Colleges, Universities and at events throughout the UK on his 20+ year practice as an artist and designer.

For press, bookings, garment hire, commissions, sales and availability, get in touch via the contact page

In Conversation

Over the course of 20 years of professional creativity, Patrick has given interviews for TV, radio, print and digital media about the nature of his artistic and fashion practice. What follows is an in depth discussion with Patrick featuring a selection of questions most frequently put to him.

Q: You’ve worked with some big names in fashion in the course of your career, though I understand the expansion of your artistic practice into fashion design is relatively recent. Can you tell us a little about your pre-fashion career?

Patrick: It is true to say my career in fashion only began in earnest around 2009. Prior to that I had an established practice as an artist/sculptor and in fact my training was in Ceramics. I studied at University of Wales Institute, Cardiff (UWIC) between 90-93 and then as a post-graduate between 97-98. I loved working with clay. It is a material you can do absolutely anything with and is infinitely variable. Clay can allow for immediacy and spontaneity, but can at times require phenomenal patience and understanding. I was fortunate to study at UWIC when I did, which was a golden period for studio ceramics. My undergraduate study allowed for the exploration of material and process with a high emphasis on build quality. The ethos at UWIC was for the expression of ideas and development of concept behind the work, particularly at MA level.

Q: Does your interest and investigation of the human body date back to this period?

Patrick: Yes, from the very beginning of my studies at UWIC, I was fascinated with human anatomy, particularly musculature and how we can alter the shape and transform be it through natural or artificial augmentative or surgical. These are themes were really the catalyst for areas of investigation which have evolved throughout my practice now for over 20 years.

Q: So how did you make the shift from ‘Ceramic Artist’ into ‘Artist’? Was it an intentional shift?

Patrick: Actually no, it wasn’t intentional. I never imagined that pursuing an MA in Ceramics would bring about the end of my ceramics career. A consequence of my post graduate studies was that I came to realize that the themes of the work and the means by which you communicate an idea must be materially appropriate; for me, concept must define the most appropriate media with which to communicate an idea. I came to realize that no matter how much I loved working with clay I could no longer justify its use in my practice. Themes I had begun to explore relating to cloning technologies, biomedical ethics and theology required a shift in the media I used, so I began to work directly with surgical devices and assemblage techniques. I’ve always worked in collage and my ceramic work I always made by assembling clay components. I used the same methods but instead used objects which already existed, which has a history of their own, building the narrative into the fabrication of the work. I began to use orthopedic implants, pharmaceuticals, dissecting and post-mortem equipment to communicate the narratives I built.

Q: Are you referring to the ‘Crown of Thorns’ and ‘Splint’ sculptures exhibited at SHOWstudio in 2013?

Patrick: Yes, and its interesting to see how work made in one facet of my creative practice has 14 years after it was created, been re-appropriated to another. I never intended the Crown to be a wearable piece, but it fitted into the vision for the Paladin collection so well.

Q: So with this transition from working exclusively with clay to pretty much anything that you felt appropriate, how long was it before you started working with fabric.

Patrick: Oh, almost immediately, not in the construction of garments but in the fabrication of the sculptural work. My first experience working with fabric was in the building of a replica psychiatrists consulting couch which involved learning upholstery techniques. I was also making the fabric roll wraps for my dissecting sets using satin, upholstery trim and even my Dad’s old overalls. In this instance, I was designing the work and outsourcing the fabric based work. A consequence of which is that I’ve never felt complete authorial ownership over those works because they had the hand of another maker in the production. This was quite a turning point for me in that I decided from this point forward, I would make all the work myself and would no longer outsource. So when it came to making the Face Corsets, I realized I was embarking on a phenomenally steep learning curve.

Q: That brings us nicely to your Face Corset work which seems to have been quite a turning point for you. How did this body of work come about?

Patrick: You are absolutely right, it was a significant turning point and in actual fact, it really changed the course of my practice and my career in many ways. This was 2002 and I was invited by the contemporary curatorial team at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, to exhibit some of my work as part of an evening long event called ‘Short Cuts to Beauty’ which hosted a series of events examining the contemporary beauty industry. However, I created the opportunity to make new work in response to the theme of the event. I proposed hypothetical notion: what if it were considered taboo to alter the structure if the face for purely cosmetic purposes? Could the face be reconfigured in the same way the shape of the body can be altered using a garment: a corset? The subsequent garments were designed to mimic the results of cosmetic surgery procedures, augmenting the lips and exaggerating the cheeks.

Q: Creating garments that alter, let alone fit the face must have been a challenge, particularly for someone who at the time, was a relative newcomer to working with fabric.

Patrick: Yes, I quickly realized how acute the learning curve I was embarking upon was. Working with a sewing machine for the first time and sticking to my commitment to make all the work myself was quite demanding. I also devised my own method of pattern making for the Face Corsets which for the time being, were designed around my face and head, it being the most readily available to me. Once I had a method of construction and fitting in place, I was able to experiment with the cut of the various panels, work with different types of fabric and really hone the finishing and detailing.

Q: What kind of responses to the Face Corsets did you receive?

Patrick: The responses really opened my eyes to the way in which a viewer will interpret and contextualize an artwork based on their own experience and preconceptions. I intentionally made the first Face Corsets using white fabric which I treated as a ‘blank and unloaded’ surface. I also shot the work in a neutral fashion, that is not to load the image generated with anything other than me wearing the pieces. The shots were more documentary if anything. On presenting the work, some viewers did (and still do) refer to my Face Corsets as ‘Masks’. In my mind, I'm not a mask maker. A mask does exactly what it suggests, it masks or hides the face of the wearer. I make work which ‘shows’ the face, but differently from how it appears normally. I don’t seek to disguise the wearer. I enable the wearer to be seen differently.

Q: I imagine there are assumptions made too about your work being allied with the fetish scene. How does that sit with you?

Patrick: It used to frustrate me that people made that assumption so readily but like I said, the viewer brings their own personal interpretation to my, and in fact any artists work. I’ve never loaded my Face Corsets nor the images in which they feature with any sexual nor fetishistic content. The viewer sees what they want to see, unless I direct them to see something very specific. If anything, I hope the Face Corsets challenge notions of what a facial garment can be, can do and can trigger.

Q: Did you see these garments as having a ‘fashion application’?

Patrick: No, not at all. In my mind, these were strictly a series of wearable artworks I was producing and if anything, they led me back into the realm of biomedical science. I had been considering augmenting the Face Corsets with commercially available facial implants. One connection led to another and eventually I wound up in a meeting with Dr Ian Thompson, a Biomaterials scientist then base at Imperial College London. He was doing amazing work casting facial implants in a material called Bioglass and we quickly realized that the casting techniques I learned but in education and in industry, could help devise methods of creating implants for the repair of patient specific injuries. This became our first major Wellcome Trust funded collaboration which allowed us to develop a production technique for the implant from which hundreds of patients have benefitted, and in tandem allowed me to further develop the Face Corsets as artworks.

Q: That must have been hugely rewarding and I guess feeds directly into the project which followed immediately after which again involved working with fabric.

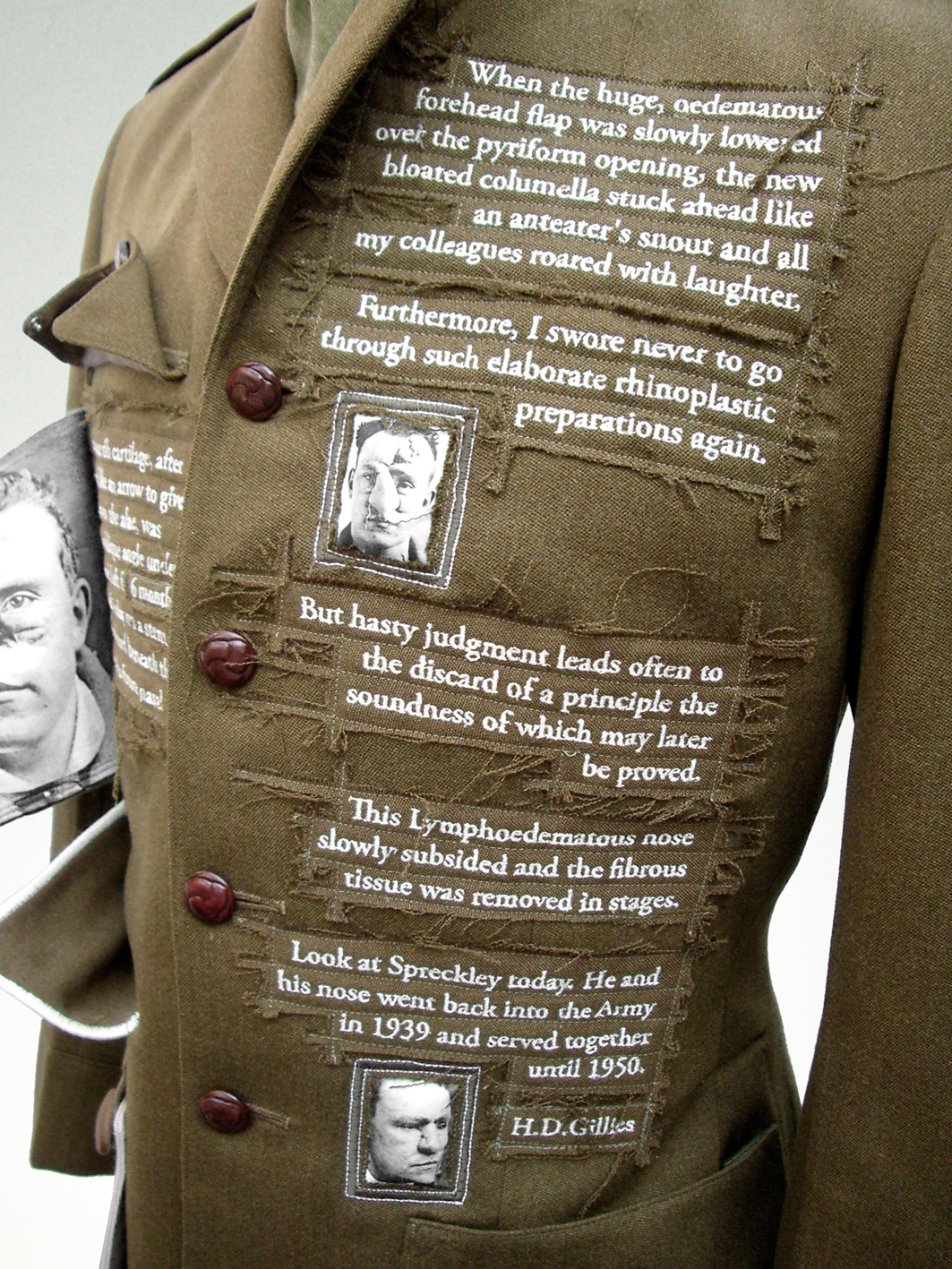

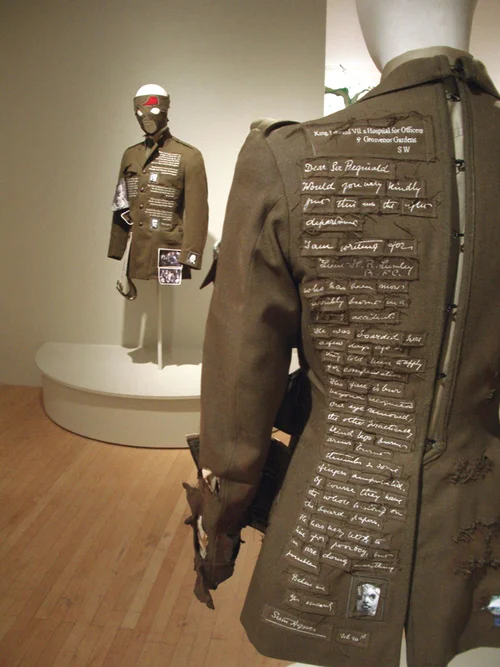

Patrick: It was and it did. I was privileged to observe a number of facial surgeries as part of the collaboration, which sparked my curiosity as to the origins of facial reconstructive surgery. It was at this point that I learned of the amazing surgery developed during WW1 by surgeon Harold Gillies. Interpreting the surgery and researching the lives of some of the men who underwent this surgery became to focus of our second Wellcome Trust funded initiative, ‘Project Facade’, this time in collaboration with Gillies Archives Curator, Dr Andrew Bamji.

Q: Regarding the uniforms you used to tell these stories, were they authentic to the period and was all the embroidery built into the work stitched by hand?

Patrick: No, the uniforms were not of the period, but they were as close as I could get and frankly, they were intended as a ‘blank canvas’ representation of the service and rank of each of the men whose stories I was interpreting. As for the embroidery, that was all digital machine embroidery but again, as with designing and making the Face Corsets, getting to grips with new equipment, software and techniques as well as creating a new visual language with which I could work was very demanding and exciting.

Q: Tracing the families of the servicemen whose stories you were interpreting and winning their trust must have been a challenge.

Patrick: It was and I had to devise all sorts of methods to raise public awareness of the project. Once I was successful in tracing families, I think they could see I was committed to telling their relatives story as honestly and directly as possible, without sensationalizing. The surgeries the men underwent were amazing in of themselves and translating these procedures and presenting these alongside fragments of family testimony gave an incredibly engaging account of what these men went through. There was no need to sensationalize. The opening night of the exhibition I curated with The National Army Museum ‘Faces of Battle’ which presented all the work in the context of telling the story of the surgery developed by Gillies during WW1 was an amazing night. Primarily because all the relatives who had contributed to the telling of the men’s stories attended the opening and it was a wonderful place to thank them all and give them a platform from which to speak about how proud they all are of their relatives who were the subject of my work. A great legacy of the project is that the uniform works continue to tour a variety of exhibitions internationally.

Q: I see the Project Façade uniforms also incorporated what look like Face Corsets but they appear to be serving quite a different purpose. What is the thinking behind these?

Patrick: I knew I wanted to incorporate some kind of facial garment in the uniform works for Project Façade, to illustrate how skin could be transported from one part of the patient, to the injury site which required grafting. However, because of some of the fetishistic interpretations of the Face Corsets, I decided that I couldn’t continue the Face Corset work and have those interpretations allied with the Project Facade work, out of respect for the families with whom I was working. So I killed-off the Face Corsets.

Q:…and what prompted their resurrection?

Patrick: I had a couple of articles published in the Times newspaper which were spotted by Stylist Simon Foxton who asked if Id consider being shot in my work for a piece for SHOWstudio. I agreed and spent an afternoon with Simon who is the most fabulously talented, perceptive and kind hearted man. The images appeared on the SHOWstudio website and a few months later, I got a call from Nick Knight asking to shoot the Face Corsets for an editorial for AnOther Magazine and the fashion film Dark Annie with Carmen Kass again for SHOWstudio. Once again, the piece was published and the requests from Stylists and Fashion Photographers to use the Face Corsets began rolling in.

Q: So at this stage, you were releasing the earlier Face Corsets designed to fit your face. What prompted you to design new work afresh and begin to explore designing for the neck.

Patrick: I wanted this second phase of the Face Corset work to be formulated around a new set of requirements. Instead of the work being designed to transform the wearers face, this time I wanted the garments themselves to be transformable and configured in different ways. I was also looking to make work which was as universally fitting as possible which was a huge challenge. This new approach was very much geared around fashion design.

Q: You do seem to have a particular materials palette in your fashion design work which is contrary to your material approach in your art work.

Patrick: To a certain degree that’s true, but I don’t feel constrained by my fashion materials palette. Although I’ve worked with silk and leather, my preferred and signature material is PVC. I love the endless possibilities this material has and it feels very sculptural. I never like to force a material into doing something it doesn’t want to, particularly the PVC. Although it’s a synthetic material, it feels like a living tissue in the way it behaves. It lends itself wonderfully to form and structure and reconfiguration.

Q: PVC features heavily in your ongoing ‘Glimm’ neckwear collections. You seem to be focusing moreso on the neckwear rather than the Face Corsets. Is this a conscious design shift?

Patrick: It’s just the way in which my work is evolving, and allowing it to evolve is an incredibly important part of my practice. Glimm for example is indeed an episodic collection. Each incarnation is an evolution of the previous collection but I intentionally build in design constraints to force myself to think around self-imposed barriers. Each final piece in the collection I allow myself to break those self imposed rules and this final piece usually informs the direction of the next Glimm incarnation.

Q: it sounds as though you are working much more intuitively with your fashion work and allows for a much greater sense of creative freedom.

Patrick: That’s absolutely right. Its all about pure shape, form and material dynamic and its incredibly liberating. I'm becoming more intrigued by garments or ‘forms’ which can be situated on, around and away from the body. Increasingly the forms I make I regard more as sculpture which alters and interacts with the silhouette of the body. I love the work of the Futurists and streamline design but try not to be too obvious with my references which sit at the back of my mind when designing but are for me a clear influence.

Q: Speaking of influences, whose work would you say inspires you?

Patrick: You know I do have my favourites. Artists Antony Gormley, Matt Collishaw, Jake & Dinos Champan, Paul Soldner, Cornelia Parker, Bill Woodrow, Yves Tanguy, Kester, Richard Notkin, Umberto Boccioni, Alberto Giacometti all have amazing bodies of work. But there are individual pieces that I see and just think that that is something inherently correct about the piece. It is absolutely perfect. Marc Quinn’s ‘Self’, Fiona Banner’s ‘Harrier’, Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Nude Descending a Staircase No:2’, Jacob Epstein’s ‘Rock Drill’ are amongst these, and if I can make one piece of work which a single person feels the same about as I feel about these works, Ill be happy.

Permission must be sought for any reproduction or use of material in this section prior to publication.

Patrick Ian Hartley. 2014

Spreckley II from Project Facade

Project Facade at The Museum of Arts and Design, New York.

Glitterbugs by Simon Foxton.

Lady Gaga by Nick Knight featuring Glimm Face Corset by Patrick Ian Hartley

Georgia May Jagger by Nick Knight featuring Glimm Rubeus neckwear by Patrick Ian Hartley